This project is available on GitHub.

Boolean Algebra

A Boolean algebra is a mathematical structure that captures the properties of logical operations and sets. Formally, it is a 6-tuple , where

- is a set of elements,

- () and () are binary operations on ,

- () is a unary operation on ,

- and are elements of , the minimum and maximum elements.

These must satisfy the usual axioms: closure, commutativity, associativity, distributivity, identity, and complements [1].

Boolean algebras show up everywhere. They form the foundation of propositional logic and are fundamental to digital circuit design and computer architecture [2].

In set theory, the standard representation is the power set of a set , denoted :

- ,

- (set intersection),

- (set union),

- (set complement),

- (empty set),

- (universal set).

This set-theoretic Boolean algebra, , is the canonical example and the starting point for what follows: a Boolean algebra over trapdoors [3]. The construction preserves the familiar Boolean algebra properties while introducing cryptographic elements for secure computations.

Homomorphisms in Boolean Algebra

A homomorphism is a structure-preserving map between two algebraic structures of the same type. For Boolean algebras, it is a function that preserves the operations and special elements.

Given two Boolean algebras and , a function is a Boolean algebra homomorphism if for all :

A homomorphism preserves structure across the mapping: you can perform operations in one algebra and have them correspond to operations in the other [4].

This matters because it lets us build a mapping between our original Boolean algebra and a new structure with cryptographic elements while still maintaining the essential properties. Operations in the trapdoor algebra remain logically consistent with standard Boolean operations.

In the following sections, I introduce a specific homomorphism that maps elements from our original algebra to a Boolean algebra over bit strings, incorporating a cryptographic hash function. This homomorphism is the foundation of the Boolean algebra over trapdoors.

The Bernoulli Model

Before introducing the Bernoulli homomorphism, I need to cover the underlying framework: the Bernoulli model.

The Bernoulli model is a probabilistic framework for representing and reasoning about approximations of values. A value can be anything from a set, whether that set is something simple like or the set of functions (I call these Bernoulli maps in the general case).

It introduces controlled uncertainty into computations, allowing trade-offs between accuracy and other desirable properties like space efficiency or security.

Formally, for any type , we define its Bernoulli approximation as

When we observe a value from the Bernoulli Model process, we write , where is the latent value of type that we cannot observe directly. The model introduces an error probability :

For a first-order Bernoulli model, for all , i.e., a constant (and usually known) probability. We say the order is . For instance, a noisy binary symmetric channel might have , meaning every observed value has a 10% chance of being wrong. For higher-order models, represents error probabilities under different conditions.

Key properties:

Propagation of uncertainty: When operations are performed on Bernoulli approximations, uncertainties combine in well-defined ways.

Trade-off between accuracy and other properties: By adjusting the probabilities, we balance accuracy against other characteristics.

Generalization to complex types: The model applies to simple types like Booleans and to complex types including functions and algebraic structures.

In this work, the Bernoulli Model provides the framework for analyzing the behavior of our cryptographic constructions.

A Boolean Algebra Over Free Semigroups

Consider the Boolean algebra

where is the powerset, is an alphabet, and is the free semigroup on , closed under concatenation:

For example, if

then

and

where is the empty string.

For Boolean algebras over finite sets, a standard approach is to represent sets as bit strings of length : the mapping where bit if the -th element (under some ordering) is in , otherwise . With bits, you can uniquely represent sets.

Our case is harder because we have a Boolean algebra over the infinitely large free semigroup . The plan is to stick with the finite bit string representation, accepting a controllable error on membership queries: the false positive rate (probability that an element not in the set falsely tests positive), assuming elements are selected randomly from .

We map elements of to bit strings in using a cryptographic hash function . If we randomly choose two elements of , the collision probability is . Collisions are the fundamental source of error, and this is what makes the approximate Boolean algebra a Bernoulli Model process.

Approximate Boolean Algebra Over Trapdoors

Consider the Boolean algebra

where $&$, , and are the bitwise , , and . We define a homomorphism :

where is a cryptographic hash function, is a secret, and .

Operations in are set operations; operations in are bitwise operations. For example, suppose with . If and , then .

We assume distributes uniformly over , so the a priori collision probability between two elements is .

If we map to via homomorphism and apply the same operations in both, we get a representation of the result in for the ground truth in . But if we query and for membership, we may see discrepancies. The homomorphism itself is approximate in the negation operation: .

These discrepancies come from the finite number () of bit strings used to represent elements of . So is an approximate Boolean algebra when used to model operations in . The approximation error is controllable by changing , and different operations have different error rates.

The cryptographic hash function is one-way: computationally infeasible (actually impossible, since the mapping is non-injective) to reverse. This is crucial for security, ensuring original elements in cannot be reconstructed from their bit string representations. Since uses , it is an approximate one-way homomorphism mapping Boolean algebra to Boolean algebra over trapdoors.

Homomorphism Properties

We have Boolean algebras and as described. We want to model operations in using via . In the proofs below, let with and .

The homomorphism must satisfy:

I show these hold for all properties except the third, which fails due to the approximate nature of the algebra. So is an approximate Boolean algebra homomorphism.

Proof of First Property: We want . From the LHS:

From the RHS:

Since $&$ and are bitwise and , only the bits corresponding to hashes appearing in both groups survive the . Only and appear in both, so:

Thus , and this generalizes to any two sets in .

Proof of Second Property: We want . From the LHS:

From the RHS:

By commutativity, associativity, and idempotency of bitwise :

So . This generalizes to any two sets in .

Proof of Fourth Property: . Trivial by definition.

Proof of Fifth Property: . Also trivial by definition.

We proved properties 1, 2, 4, and 5. Note that we did not show identities like

since is one-way and has no inverse. Now I show that property 3 does not hold.

Disproof of Third Property: We want to disprove . Starting from the LHS:

which is an infinite set containing everything in except , , and . It includes , , , and so on.

Assuming distributes these uniformly over bit strings of length , by the pigeonhole principle, every bit string in has multiple elements hashing to it. Applying to the complement:

the result is all ones:

From the RHS:

This is a finite number of elements OR-ed together, then bitwise NOT-ed. Due to the hash function, some bit positions will be 1 and others 0, giving a bit string that is not all ones:

So . As increases, the probability that approaches 1, and asymptotically as the third property holds. But in general, is only an approximate Boolean algebra homomorphism.

Single-Level Hashing Scheme

In the next section I introduce a two-level hashing scheme that reduces space complexity. First, I derive the space complexity of the single-level scheme for representing free semigroups as “dense” bit strings of size . The punchline: to keep false positive rates on membership () and subset () constant, the number of bits must grow exponentially with the number of elements. This limits the scheme to very small sets. The two-level scheme addresses this.

I derive the single-level scheme first because it is theoretically interesting and provides the foundation for the two-level scheme.

Relational Predicates

Here I view the Boolean algebra in a set-theoretic context and define the fundamental predicates: membership and subset relations.

Set Membership

Set membership tests whether an element is in a set. Boolean algebra has:

defined as

where is the set indicator function.

For approximate Boolean algebra :

defined as

This means we test membership by checking that if has a bit set to 1, that bit must also be set in . This permits false positives: may test true even if .

When we take the union of two sets, we take the bitwise of the two bit strings. Consider two edge cases. The empty set has representation , and the singleton has representation . Their union:

Similarly, the universal set with representation and singleton :

Now consider the union of two singletons and :

Let and . The probability that the -th bit is 1 in is , same for . The probability that the -th bit is 1 in :

By De Morgan’s laws:

By independence:

and since is uniform over , each bit is 0 with probability :

Generalizing to unions of unique singletons:

Using the approximation for small , with :

The probability that all bits are 1:

Since as , the union of singletons converges in probability to the universal set . At that point, further unions change nothing.

False Negatives and False Positives

Suppose we have a set and want to test if a randomly chosen is a member. Let be the hash of with -th bit . If actually is in , all bits set to 1 in are also 1 in by construction. The false negative rate is .

If is not in , a false positive may occur. For a false positive, every bit where must also be 1 in . This is logical implication:

Equivalently:

The probability:

With uniform, . After unions, . Therefore:

For a false positive, this must hold for all bit positions:

Asymptotic False Positive Rate

Using the approximation with :

which holds even for relatively small . In Big-O notation, fixing :

meaning approaches 1 exponentially fast as increases.

Space Complexity

Rewriting as a function of and :

For small , , so:

Holding constant:

meaning the number of bits must grow exponentially with the set size to maintain a fixed error rate. This limits the scheme to very small sets.

The false positive probability depends on both (set size) and (bits in the representation). Unsurprisingly, false positives increase with and decrease with , but now we have a model that quantifies the relationship.

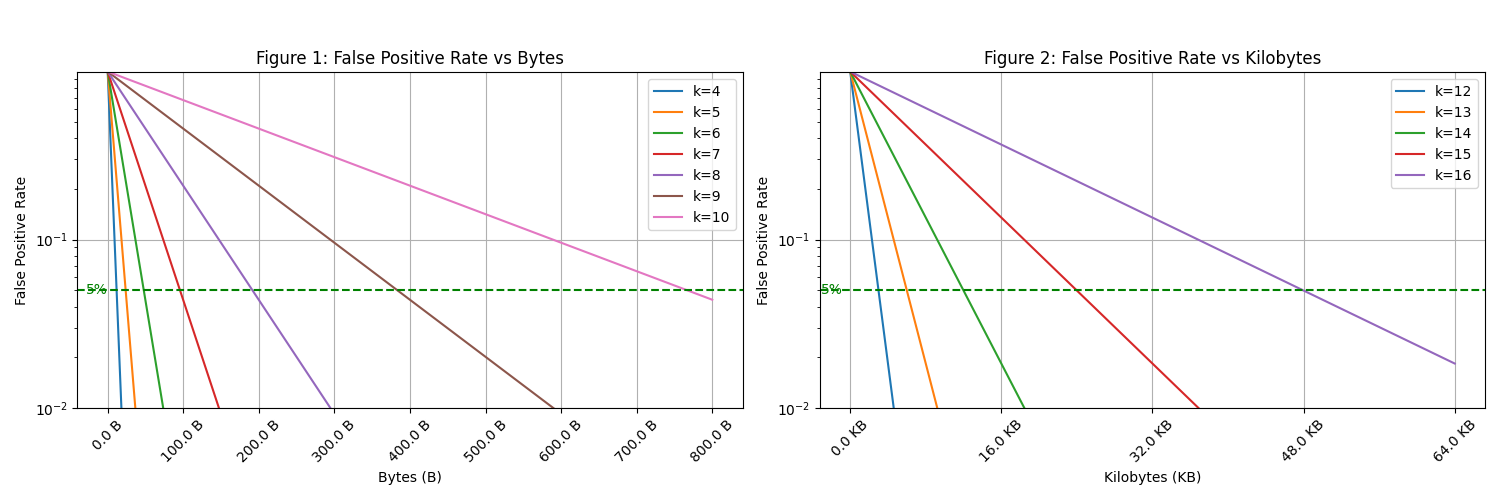

In Figure 1, the false positive rate decreases exponentially as the byte size of the hash increases for smaller sets of elements (k=4 to k=10). In Figure 2, we observe the false positive rate behavior over larger kilobyte sizes for larger sets (k=12 to k=16). The green dashed line represents the 5% false positive rate threshold. As k increases, achieving this threshold requires significantly more space, highlighting the trade-off between set size and hash size.

Subset Relation

The subset relation predicate:

defined as

In approximate Boolean algebra :

defined as

which looks identical to the set-indicator function but has different error probabilities.

Let and be bit strings for and . The probability that is a subset of requires for all . Each is logical implication:

equivalently

The probability:

where and are the sizes of and .

For a false positive on , this must hold for all positions:

Approximating:

and applying the approximation again to :

In Big-O with fixed :

where . So approaches 1 exponentially fast as increases. Consistent with the membership relation analysis.

Since equality can be written as , the false positive rate for equality is the product of the false positive rates for both subset directions.

Two-Level Hashing Scheme

The single-level scheme requires exponentially growing bit strings. To address this, I introduce a two-level scheme that reduces space complexity for practical use.

The construction:

- A hash function outputs bits.

- The first bits determine which bin the element goes in ( bins total).

- The remaining bits represent the element within the bin.

- Total: bits.

False Positive Rate

Membership Relation

Assume elements are in the set and we test membership of . No false negatives, as before. A false positive occurs when:

- With probability , maps to some particular bin.

- That bin, represented by bits, has an expected elements.

- Using the earlier derivation for the per-bin false positive rate:

Fixing and :

asymptotically the same as the single-level scheme, but much more practical for reasonably large sets.

Space complexity: bits, or bits per element, for false positive rate .

In Figure 3, we show the false positive rate for different values of and .

C++ Implementation: Single-Level Hashing Scheme

Here is a C++ implementation modeling the Boolean algebra over trapdoors. I generalize trapdoors to any type , parameterized over hash size .

Each trapdoor<X,N> represents a value of type X as an -byte hash using a cryptographic hash function. It models equality as a Bernoulli Boolean with a false positive rate of and a false negative rate of . In Bernoulli Model notation:

where is a trapdoor of type and the latent value is the equality predicate.

The trapdoor_set<X,N> class represents an approximate Boolean algebra over trapdoors. It extends trapdoor<X,N> with these operations:

empty_trapdoor_set<X,N>()returns the empty set ().universal_trapdoor_set<X,N>()returns the universal set ().operator+(trapdoor_set<X,N> const & x, trapdoor_set<X,N> const & y)returns the union ().operator~(trapdoor_set<X,N> const & x)returns the complement ().operator*(trapdoor_set<X,N> const & x, trapdoor_set<X,N> const & y)returns the intersection ().empty(trapdoor_set<X,N> const & xs)returns a Bernoulli Boolean for emptiness, with false positive rate .in(trapdoor<X,N> const & x, trapdoor_set<X,N> const & xs)returns a Bernoulli Boolean for membership. See the Relational Predicates section for details.

For closure, the class has a hash member function returning the stored hash, enabling composition of operations (e.g., creating a powerset of trapdoor_set objects).

#include <array>

template <typename X, size_t N>

struct trapdoor

{

using value_type = X;

/**

* The constructor initializes the value hash to the given value hash.

* Since the hash is a cryptographic hash, the hash is one-way and so we

* cannot recover the original value from the hash.

*

* This also models the concept of an Oblivious Type, where the true value

* is latent and we permit some subset of operations on it. In this case,

* the only operation we permit is the equality and hashing operations.

*

* @param value_hash The value hash.

*/

trapdoor(std::array<char, N> value_hash) : value_hash(value_hash) {}

/**

* The default constructor initializes the value hash to zero. This value

* often denotes a special value of type X, but not necessarily.

*/

trapdoor() { value_hash.fill(0); }

std::array<char, N> value_hash;

};

/**

* The hash function for the trapdoor class. It returns the value hash.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto hash(trapdoor const & x)

{

return x.value_hash;

}

/**

* Basic equality operator. It returns a Bernoulli Boolean that represents

* a Boolean value indicating if the trapdoors are equal with a false positive rate

* of 2^{-8 N}. Different specializes of the trapdoor class may have different

* false positive rates, but this is a reasonable default value.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto operator==(trapdoor const & lhs, trapdoor const & rhs) const

{

return bernoulli<bool>{lhs.value_hash == rhs.value_hash, -8*N};

}

/**

* The `or` operation in the Boolean algebra over bit strings.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto lor(trapdoor lhs, trapdoor const & rhs)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

lhs.value_hash[i] |= rhs.value_hash[i];

return lhs;

}

/**

* The `and` operation in the Boolean algebra over bit strings.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto land(trapdoor lhs, trapdoor const & rhs)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

lhs.value_hash[i] &= rhs.value_hash[i];

return lhs;

}

/**

* The `not` operation in the Boolean algebra over bit strings.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto lnot(trapdoor x)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

lhs.value_hash[i] = ~lhs.value_hash[i];

return lhs;

}

template <typename T>

auto minimum() { return std::numeric_limits<T>::min(); }

template <typename T>

auto maximum() { return std::numeric_limits<T>::max(); }

/**

* The `minimum` operation in the Boolean algebra over trapdoors

*/

template <typename trapdoor<typename X, size_t N>>

auto minimum() { return trapdoor<X,N>(); }

/**

* The `maximum` operation in the Boolean algebra over trapdoors

*/

template <typename trapdoor<typename X, size_t N>>

auto maximum()

{

trapdoor<X,N> x;

x.value_hash.fill(std::numeric_limits<char>::min())

return x;

}

/**

* The trapdoor_set class models an approximate Boolean algebra over trapdoors.

* It is a specialization of the trapdoor class that implements additional operations

* that can take place over the domain of trapdoor and trapdoor_set.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

struct trapdoor_set: public trapdoor<X,N>

{

trapdoor_set(

double low_k = 0,

double high_k = std::numeric_limits<double>::infinity()),

std::array<char, N> value_hash)

: trapdoor<trapdoor_set<X,N>,N>(value_hash),

low_k(low_k),

high_k(high_k) {}

trapdoor_set() : trapdoor<trapdoor_set<X,N>,N>(), low_k(0), high_k(0) {}

trapdoor_set(trapdoor_set const &) = default;

trapdoor_set & operator=(trapdoor_set const &) = default;

double low_k;

double high_k;

};

/**

* The size (cardinality) of the latent set (the set the trapdoor_set represents).

*

* @param xs The trapdoor_set.

* @return The size range of the set.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto size(trapdoor_set<X,N> const & xs)

{

return std::make_pair(xs.low_k, xs.high_k);

}

/**

The union operation.

*/

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto operator+(

trapdoor_set<X,N> const & xs,

trapdoor_set<X,N> const & ys)

{

return trapdoor_set<X,N>(lor(xs, ys).value_hash,

std::max(xs.low_k, ys.low_k), xs.high_k + ys.high_k);

}

template <typename X, size_t N>

void insert(trapdoor<X,N> const & x, trapdoor_set<X,N> & xs)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

xs.value_hash[i] |= x.value_hash[i];

// since x could already be in xs, we do not increment the low_k

// only the high_k

xs.high_k += 1;

}

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto operator~(trapdoor_set<X,N> x)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

x.value_hash[i] = ~x.value_hash[i];

// assume |x| in [a, b]

// then |~x| has the following analysis.

// - if |x| = a, then |~x| = |U| - a, where |U| is universal set

// - if |x| = b, then |~x| = |U| - b

// so, |~x| in [|U|-b, |U|-a]

x.low_k = maximum<X>() - x.high_k;

x.high_k = maximum<X>() - x.low_k;

return x;

}

template <typename X, size_t N>

auto operator*(

trapdoor_set<X,N> const & x,

trapdoor_set<X,N> const & y)

{

return trapdoor_set<X>(x.value_hash & y.value_hash,

0, // intersection could be empty

std::min(x.high_k, y.high_k) // one could be a subset of the other

);

}

template <typename X, size_t N>

bernoulli<bool> in(trapdoor<X,N> const & x, trapdoor_set<X,N> const & xs

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

if ((x.value_hash[i] & xs.value_hash[i]) != x.value_hash[i])

return bernoulli<bool>{true, 0};

// earlier, we showed that the fp rate is (1 - 2^{-k})^n

return bernoulli<bool>{false, };

}

/**

* The subseteq_B predicate, x \subseteq_B y, is defined as x | y = x.

* It has an false positive rate of eps = (1 - 2^{-(k_1 + k_2 log 2)})^n

* which we approxiate as eps ~ e^{-n e^{-(k_1 + k_2 log 2)}}.

* we store the log(eps) instead: -n e^{-(k_1 + k_2 log 2)}

*/

template <typename X>

bernoulli<bool> operator<=(

trapdoor_set<X> const & x,

trapdoor_set<X> const & y)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

if ((x.value_hash[i] & y.value_hash[i]) != x.value_hash[i])

{

return bernoulli<bool>(false, 0); // false negative rate is 0

}

// earlier, we showed that the fp rate is (1 - 2^{-(k_1 + k_2 log 2)})^n

return bernoulli<bool>{true, };

}

template <typename X>

bernoulli<bool> operator==(

trapdoor_set<X> const & x

trapdoor_set<X> const & y)

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < N; ++i)

if (x.value_hash[i] != y.value_hash[i])

return bernoulli<bool>{false, 0.5};

}

Appendix

Marginal Uniformity

Suppose we have a probability distribution over elements (unigrams) in such that

is the probability of being generated from some data generating process . We can transform homomorphism to map each to multiple hashes inversely proportional to , satisfying

even if and are significantly different.

When doing a membership query, we uniformly sample one of these representations so that the unigram distribution of elements in is uniform. This is a kind of marginal uniformity.

However, this approach has serious shortcomings:

Only the marginal distribution of unigrams is uniformly distributed. Correlations in the joint distributions of , such as bigrams, are not accounted for. We can apply the transformation to larger sequences, but space complexity grows exponentially with sequence length for a fixed false positive rate. In practice, even the unigram model may need approximation due to space limits.

When we apply Boolean operations on an untrusted system, it cannot be given distribution information about elements in . This means Boolean operations like and cannot be performed on the untrusted system, only relational queries like and .

Discussion